Tales from the Front - What Teachers Are Telling Me at AI Workshops

Real conversations, real concerns: What teachers are saying about AI

“Do I really have to use AI?”

No matter the school, no matter the location, when I deliver an AI workshop to a group of teachers, there are always at least a few colleagues thinking (and sometimes voicing), “Do I really need to use AI?”

Nearly three years after ChatGPT 3.5 landed in our lives and disrupted workflows in ways we’re still unpacking, most schools are swiftly catching up. Training sessions, like the ones I lead, are springing up everywhere, with principals and administrators trying to answer the same questions: Which tools should we use? How do we use them responsibly? How do we design learning in this new landscape?

But here’s what surprises me most: despite all the advances in AI technology, the questions and concerns from teachers remain strikingly consistent. Sure, there are moments of excitement at the workshops and delightful discoveries. But just as often, there’s resistance, confusion, and very real, practical fears that rarely make it into the shiny, optimistic narratives about AI in education.

In this article, I want to pull back the curtain on those conversations. These concerns aren’t signs of reluctance - they reflect sincere feelings. And they deserve thoughtful, honest answers.

How my workshops are structured

To provide context for the feedback I receive, let me share how I approach these training sessions and why this methodology has proven effective.

At schools, there are usually three groups of educators: those with experience - who use AI tools regularly for prepping activities for class, then there are those who may have tried it once but do not use regularly because they saw no need or were disappointed at the unsatisfactory result, and then there are those who have never used AI at all, never written a prompt, never even considered using it.

I begin by laying a foundation - demonstrating why genAI is here to stay (and it's not going away) and why every educator needs to be AI literate. I show why detectors don't work reliably and mention the current capabilities of AI tools (here I have to update my slides almost weekly!). Surprising for most, I encourage all to have at least 3 chatbots for text and 2 chatbots for images in their toolbox, since each has different strengths and limitations that become apparent when comparing results side-by-side. Most have never heard of alternatives beyond ChatGPT.

Then, depending on the time frame, I touch on prompting, how to motivate students to use AI only for help and not for the whole task, then I show teacher tool portals and how they can use virtual classrooms with students safely. I have them test tools at the workshops so they can get a feel for them themselves. There are usually a few AHA-moments when they encounter tools or like NotebookLM or Suno.com.

I conclude by providing a curated resource list and encouraging teachers to start with just one small implementation in their classroom, rather than overwhelming themselves with a complete workflow overhaul.

Of course, even with this carefully structured approach, I get many questions and hear diverse reactions - which brings me to the core concerns I keep encountering.

Permission, Privacy, and the AI Tightrope

The question I hear most frequently focuses on permission and compliance. Teachers want to know if they're even allowed to use AI tools with minors in their classrooms.

The reality? It's complicated, and regulations continue to evolve as educational systems catch up to technological advancements.

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, sets the minimum age at 13 years, but anyone under 18 needs parental consent to use the service. Additionally, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU sets different age limits for giving consent to online services, usually between 13 and 16 years, depending on the country. For example, in Austria and Italy, the minimum age is 14. If a student is younger than the required age, they need a parent's permission.

In schools, ChatGPT and similar AI tools can be used under teacher supervision, even with younger students, as the school is responsible for ensuring that data protection rules are followed. So, with the right consent and guidance, young people across Europe can safely explore and learn with AI tools. The key is using these tools in teacher-guided and supervised contexts.

Thus, I explain how my students (under 18 years) use ChatGPT and other tools - with parental consent and under my close supervision. Indeed, the solution many educators have found is to:

Use school-approved tools whenever possible (some districts purchase licenses)

Avoid entering any personally identifiable student information

Consider AI tools that offer educational accounts with stronger privacy safeguards

Create classroom guidelines about what information is safe to share

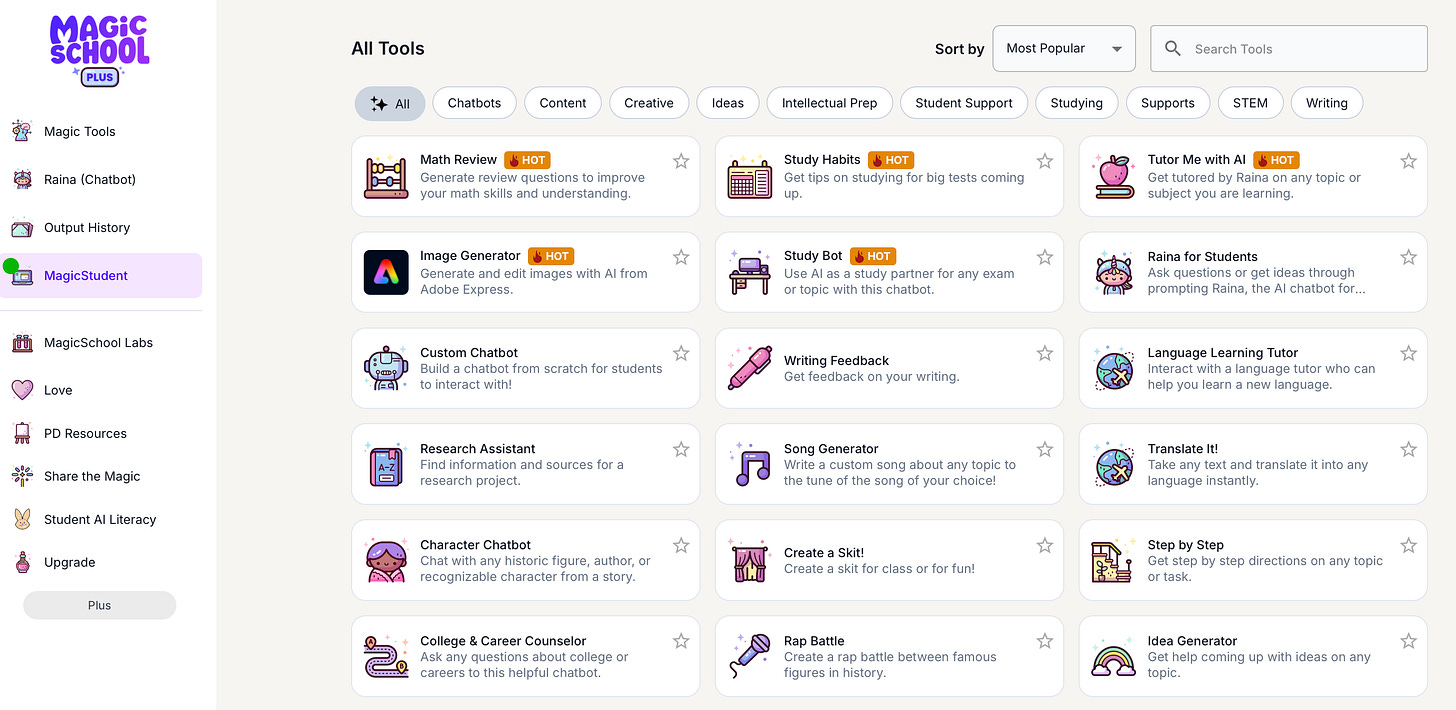

With platforms like magicschool.ai, it's possible to create a controlled online environment where teachers can permit specific AI tools for specific educational purposes. Students simply receive a link and enter a code to access the space - no need for them to log in with personal accounts or enter their real names. This directly addresses one of the most common concerns I hear: "Where is all this student data being stored, and who has access to it?"

This approach exemplifies what I've come to call "supervised integration" — bringing AI into the classroom in controlled, thoughtful ways that protect student privacy while still providing valuable learning experiences.

Bottom line: although navigating questions of data privacy can be complex, this complexity shouldn't prevent educators from incorporating AI tools altogether. AI literacy for students is paramount - they can only develop this literacy when they're taught how to use these tools effectively and ethically by educators who understand both the capabilities and limitations of the technology.

Lost in the AI Jungle: Finding the Right Tools

Another major concern that emerges often revolves around tool selection, reliability, and cost.

"There are too many options!" exclaimed a clearly overwhelmed English teacher during our last session. "Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot... and they all seem to be the same. Do I need to pay for a pro account? Can I trust them? Which one should I actually use?"

These questions reflect the genuine feeling many educators feel. After all, not many have the time to follow the latest updates or test all tools on their performance - particularly when these tools are updated almost monthly with new features and capabilities.

My advice has been consistent: Start simple. Choose one or two tools and get comfortable with them before branching out. For most teachers, either ChatGPT, Claude or Gemini provides an excellent entry point due to their user-friendly interfaces and educational applications. Each has different strengths and brings unique capabilities, making them well-suited to different tasks and environments.

ChatGPT is especially strong in creative writing, brainstorming, and versatile content generation. It’s widely used for tasks like drafting, editing, coding, and coming up with new ideas.

claude.ai excels at nuanced, complex explanations, advanced reasoning, and summarizing or analyzing large documents. It is particularly effective for deep analysis and tasks that require careful ethical consideration.

gemini.google.com stands out for its seamless integration with Google Workspace for Education tools such as Docs, Sheets, and Classroom. This makes it a popular choice in educational settings, where it supports drafting, summarizing, and creating visuals directly within Google’s ecosystem.

In Austria, many use CoPilot in Microsoft Teams, which has recently received features especially interesting for educators such as Agents, Pages (separate document repositories that are shareable), a Prompt Gallery and a place to store personal prompts.

Companies are not making it easy for beginners to understand which model does what and what value paying provides versus using free versions. I typically explain that paid versions provide more reliable responses, fewer usage restrictions, and access to the most current models. For departments or schools considering serious integration, pooling resources for a shared professional account often makes the most sense.

As for reliability — this is where the frustration peaks, especially among literature and humanities teachers.

"I asked it for sources on Kafka and got completely fabricated references!" one literature teacher vented. "How am I supposed to trust this in my classroom?"

This highlights a critical challenge with AI tools: they sometimes "hallucinate" information, generating convincing but entirely fictional content. Many educators I've spoken with see this as a dealbreaker.

"If these tools can't distinguish between fact and fiction," argued a history teacher firmly, "they have no place in education. I can't recommend something to students that might confidently present false information as truth. The potential for misinformation is too dangerous."

I often respond by demonstrating a simple classroom exercise: asking the same question to multiple AI tools, then having students compare the responses and identify inconsistencies. This highlights a critical teaching moment. I see this as a positive. Hallucinations are going to be hard to overcome. But this encourages information literacy. The savvy educator uses this limitation as a teaching opportunity — demonstrating critical thinking skills, fact-checking, and source verification that students desperately need to develop in our information-saturated world.

The tool selection dilemma is compounded by what is perhaps the most practical constraint of all – the limited time and bandwidth teachers have at their disposal.

Time-Strapped and Tech-Tired: The Realities of Teacher Workloads

Perhaps the most poignant concern comes from teachers already stretched thin by existing demands.

"This all sounds great," a veteran teacher told me, arms crossed, "but I'm already drowning in curriculum requirements, test prep, and extensive correcting sessions. When exactly am I supposed to learn all this new technology? And teach it? And prevent students from using it to cheat?"

The exhaustion in her voice was palpable, and I've heard it echoed in workshops in many different contexts.

The technical barriers only compound this frustration. During a recent hands-on workshop, I witnessed several teachers struggling with the most basic digital prerequisites.

"I don't have a Google account," one teacher admitted sheepishly. "I've never needed one for my subject."

"I have one but I can't remember the password," another chimed in. "There are too many accounts to keep track of already."

As the workshop progressed, I noticed several participants falling behind, unable to keep pace with even basic demonstrations. "Could you slow down?" one asked. "Some of us aren't as comfortable with technology."

These moments reveal a crucial gap in professional development: we're asking teachers to integrate sophisticated AI tools when many haven't received adequate support for fundamental digital literacy. It’s a powerful reminder for me not to expect the same level of skill from others and to adapt accordingly.

Another common roadblock emerges from institutional inertia. "Our administration hasn't given us any directive to use these tools," a cautious department head explained. "Without official guidance, I'm not going to recommend something that might create problems down the line."

This wait-for-permission approach, while understandable, often leads to educational stagnation as schools delay engaging with tools that students are already using extensively outside the classroom.

When confronted with these very real constraints, my response is always twofold: First, I acknowledge the legitimate burden. Teaching is already one of the most demanding professions, and adding "master cutting-edge AI" to the requirement list isn't fair without proper support and time allocation.

I offer a perspective shift: AI tools can potentially reduce workloads rather than increase them. When properly implemented, they can help with:

Generating differentiated learning materials for various student needs

Providing quick feedback on basic elements of student work

Creating scaffolded learning activities that previously would have taken hours to prepare

Assisting with administrative tasks like email drafting and planning

One mathematics teacher shared how he uses AI to generate multiple versions of practice problems at different difficulty levels — something that used to consume his evenings. "It's given me back time to focus on the human aspects of teaching," he explained, "like really connecting with struggling students."

Still, it has to be said. Beginners need MORE time to get to a level of comfort where they can use it with students - so in the short term, genAI is NOT providing relief but adding to an already full plate. Admins would do well to carve out dedicated time for those who need it, rather than expecting teachers to somehow find extra hours in their already packed schedules.

AI and the Heart of Education: Encouraging Effort, Not Replacing It

Beneath all these practical concerns lies a deeper philosophical question that many educators wrestle with: What does AI mean for the development of student thinking and effort?

A language teacher approached me after a workshop, visibly frustrated. "I barely have enough time to cover the curriculum requirements as it is," she explained. "I can't allocate precious class time just for writing exercises that they should complete at home anyway. When am I supposed to fit this in and still prepare them for exams?"

Her concern reflects the very real time constraints educators face when trying to incorporate new technologies while still meeting established learning objectives.

"If they can just ask ChatGPT to write their essays," another teacher challenged, "why would they ever learn to write themselves? Aren't we just enabling laziness?"

This question strikes at the core of educational philosophy. My response is to ask teachers to reflect on the purpose of education itself. Is it about producing specific artifacts (essays, problem sets, reports) or developing flexible minds capable of navigating an uncertain future?

Another art teacher dismissed some AI applications entirely. "All this image generation stuff is a nice-to-have," she scoffed. "It has no real no added value for serious learning. Students need to learn actual skills, not just prompt an AI to make pretty pictures."

I've heard variations of this sentiment many times, and it raises important questions about distinguishing between novelty and genuine educational value.

The most forward-thinking educators I've worked with are reimagining assignments entirely. Instead of fighting an unwinnable battle against AI use, they're creating tasks that incorporate AI as a tool while still developing critical student skills:

Having students critique and edit AI-generated writing rather than starting from scratch

Asking students to prompt AI systems and then analyze, fact-check, and improve the responses

Using AI-generated content as a starting point for deeper discussion and analysis

Teaching students to collaborate with AI tools rather than either avoiding them or relying on them entirely

"I've started having students use AI to generate a first draft," shared a writing teacher, "but then we work on the human elements AI can't replicate — the personal voice, the emotional resonance, the unique perspective. It's actually leading to more thoughtful discussions about what makes writing distinctly human."

Moving Forward Together

As I conclude my workshops, I try to leave teachers with both practical tips and encouragement. The AI revolution in education isn't slowing down, but it doesn't have to be overwhelming.

The most successful approach I've observed combines:

Start small — Begin with one tool, one application for your students and context.

Learning By Doing With Students — Be transparent with students about exploring these tools and solutions together.

Focus on thinking skills — Emphasize the thinking processes that remain uniquely human. Make human thinking (and thus learning) visible.

Connect with colleagues — Share successes, failures, and questions with other educators.

One teacher's parting words have stayed with me: "I came in feeling like AI was going to replace what I do. I'm leaving seeing it as something that might actually let me focus more on why I became a teacher in the first place — to connect with students and help them grow as thinkers."

The road ahead contains challenges, certainly. But I truly believe educators have what it takes to adapt to this new reality. And while we may not have all the answers and solutions to the challenges AI poses, I’m hopeful that this is an opportunity for us to grow and focus on how to help our learners meet their goals.

What concerns are you hearing from teachers in your context? How are you navigating these new waters? I'd love to continue the conversation in the comments below.

Thanks for reading!

Images generated by ChatGPT 4o.

I also enjoyed reading this, and it gave me a lot to consider. Teachers in Austria and elsewhere have widely different comfort levels and experiences with various technologies, and you covered many scenarios.

One part that stuck out was the “hallucination” issue. I tend to agree with Jordan Peterson and some philosophers that exact facts aren’t as important as the feeling/story/moral we get from learning. As a concrete example, predating mass AI, an English textbook for Austria contained some laughably inaccurate information on a reading sample about South Africa. It was clearly just whoever wrote it patching together ideas about how racism was bad, and stitching these ideas together in a way that made sense to someone who only has a vague idea about the topic. (Like if you were to read in a German textbook that National Socialism began in the 1800s to stop Turkish guest workers from stealing auto factory jobs in Graz, you would think WTF is this nonsense?) So personally, I would trust AI more than humanity, because I’ve seen enough examples like this. But yes, comparing side by side and keeping a wary eye out is important.

Thanks for sharing your workshop approach with K-12 teachers! I mostly work with college teachers, but all of this still pertains: the gentle introduction, hands-on encouragement, learning with students, and connecting with colleagues. I appreciate how you take teachers' anxieties and concerns seriously! They didn't ask for this, but have to respond.